The return

Jenn will be returning to the Gulf of Mexico to continue the coverage of the BP Deepwater Horizon Gulf oil spill August 4-10,

one month after the original trip.

If you are interested in content, you can contact her via

email: Jenn@jennleblanc.com

She will be documenting:

Venice/Fort Jackson/Buras/Grand Isle LOUISIANA,

Long Beach/Gulfport/Biloxi MISSISSIPPI,

Orange Beach/Fort Morgan/Dauphin Island ALABAMA.

Vegetable oil, mayonnaise help clean sea turtles of crude oil

By Noelle Leavitt

One of two Kemp's Ridley sea turtles on display at the Audubon Nature Institute in New Orleans. The turtles are two of 112 rescued so far, and cleaned up from oil contamination from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

New Orleans, LA — Hundreds of sea turtles now live in a different world.

The Gulf of Mexico oil spill sent them from nesting along the gulf shores, into oil rehabilitation at various locations in Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama and Florida.

Despite the doom and gloom about what the BP oil spill has done to their natural habitat, the Audubon Nature Institute in New Orleans prides itself on its care for the endangered species.

The institute has treated 112 sea turtles since the BP oil rig exploded on April 20, and only three of those turtles have died, said Michele Kelley, Audubon Nature Institute‘s stranding coordinator for the state of Louisiana.

“We’ve had a 99 percentile success rate,” Kelley said.

But it’s not been easy. Everyday, Kelley and a rotating crew of around 50 trained workers, look for different remedies to treat and clean sea turtles of the crude oil that pollutes their internal and external organs.

“There is no historical data on how hydrocarbons effect sea turtles,” Kelley said, adding that finding the right treatment is difficult.

“Not only are we doing it, we’re also writing the book on it as we go, and we’re having to test things. We’re constantly changing and trying new things, she said.”

Vegetable oil and mayonnaise are currently the best way to rid turtles of the thick and sticky oil that contaminates their waters in the Gulf.

“You could hang wallpaper with that stuff,” Kelley said of the crude oil.

The oil has engulfed a number of barrier islands along the Gulf of Mexico, where many sea turtles nest and live. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, along with many other organizations, collect oil-effected sea turtles and transport them to the appropriate recovery institute.

“When they come in, we get a photo id on the animals, we get them tagged — when dealing with a hundred turtles, we need to know who’s who. Vets look at the turtles to determine their overall health,” Kelley explained.

After the vets log the health of each turtle, removing the crude oil begins.

“We use vegitable oil to begin with, because oil binds with oil. Water and oil don’t mix, but oil and oil do,” Kelly said. “We pull it off and then we use Dawn (soap). We’ll actually put mayonnaise in their eyes to remove the oil from their eyes, and then open their mouths and swab out oil with mayo in their mouths.”

Next, they soak the turtle down, remove all the vegetable oil and crude oil and begin removing the contaminates from its digestive system.

“We’re using mayo mixed with cod liver oil, and that seems to be binding with the oil in their digestive system, which is what we need,” Kelly said. “The longer they’re exposed to the oil — both on the outside and on the inside — it starts to lead to secondary infections, such as pneumonia.”

Two of the recovered — once oiled and now healthy —

The majority of the sea turtles that have been treated at the New Orleans institute are the Kemp’s Ridley species, which are the smallest marine turtle in the world, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

“Guess what, the gulf of mexico is their home,” Kelly said. “Kimp’s Ridley’s are critically endangered, which means there’s less than 5,000 nesting females in the wild — and guess where they nest? The coast of mexico and texas right now.”

The two on display at the massive aquarium in New Orleans, give onlookers an upfront account of a recovered sea turtle.

One of two Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles on display at the Audubon Nature Institute in New Orleans. The turtles are two of 112 rescued so far, and cleaned up from oil contamination from the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Long Beach into Night : 3

Workers use shovels to gather and scoop the orange gooey mousse into plastic bags to be hauled to the local trash dump. Night operations on Long Beach in Long Beach and Pass Christian started July 7, 2010 and this was the third consecutive night of work in the same area. The workers are tired but in good spirits, they are not allowed to speak with us. For us to witness the work we must stay out of their way and enter and exit the containment area through the decon tents. They work hard until someone comes and tells them to stop for a break or a shift change. They keep going, working on the seemingly endless piles of oil that come ashore with the tide.

The oil collected is taken to the local dump. That’s right, it’s going into the Pecan Grove Landfill in Pass Christian, Miss.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

FORT MORGAN, Ala.

The ‘sugar sand’ beaches at Fort Morgan used to be white according to one clean-up worker. Fort Morgan is a State Historic site as well as an upscale beach community. One of the interesting aspects of Fort Morgan are the endangered Alabama Beach Mice. They live in small burrows in the sand, and only come out at night. When they dig out the burrow the contrast between the clean sand below and dirty sand above becomes obvious.

The beach mice are endangered due to dissappearing habitat, the effects of the oil spill on their only remaining habitat are, as yet, unknown. The beach in this area is not inundated with the orange oil mousse that we have seen much of in Mississippi, but instead with the black tar balls that the burrows are surrounded with.

Photo by Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

ORANGE BEACH, Ala.

Boom operations in Cotton Bayou and Bayou Saint John. The white boom is called sorbent boom and is dragged behind the boats with pompoms attached that collect any surface oil. The different colors of boom are for different types of water, and use, but every boom has universal attachments so they can be linked without problems, regardless of manufacturer. Vehicles of Opportunity drag boom back and forth across the inlets to different areas to prevent as much contamination into the bayous and harbors as possible. The brown discoloration in the water is not oil but tannins which are eaten by the local fish and important to the habitat.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

BP to build a large barrier on Dauphin Island to block oil

DAUPHIN ISLAND, Ala. Crews worked to clean up beached oil that washed ashore at Dauphin Island while people sunned and swam all around them. Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

The oil spill has prompted BP to give the state of Alabama $17 million to build a mile-long sand and rock barrier designed to block oil from washing upon the state’s shoreline, according to a BP spokesperson.

The barrier is currently being built on the west end of Dauphin Island, which is a few miles south of Mobile, AL.

Alabama’s Department of Environmental Management is overseeing the project that will be a mile and a quarter in length and 50-feet wide.

Huge-boulder rocks are shipped to Dauphin Island everyday by barges and, after they’re placed in the water, sand is spread over them to create a manmade island, said Henry De La Graza, a BP spokesman.

Dauphin Island has roughly 1,700 people who live there, and each day BP work crews clean the beaches of tar balls.

“We had 800 workers combing the beaches since yesterday,” De La Graza said. “We picked up around 12,000 pounds of tar balls, which is a light day for us.”

A small percentage of the tar balls are recycled, but most of them are shipped to a landfill.

Tourism has taken quite a dip on the Island.

Karl Hoven, who owns Dauphin Island Cheveron and Grill said his business has dipped 75 percent since the oil slick.

“It has slowed down considerably,” he said. “The tourists is what makes us from the middle of March to the end of September. If you don’t make your money then, you have a long hard winter.”

Although tourism has dropped, locals still swam in the oil contaminated waters.

Mobile, AL resident Sheila Clark, her daughter Sara, 13, and friend Jaimee Orrell, 12, visited Dauphin Island July 8. BP clean-up crews combed the beaches while they enjoyed the sunny weather. She wanted to witness what the oil was doing to the beaches first hand.

“All we’re seeing is these little globs right here. We’re not seeing what’s under the water,” Clark said. “Our Mobile industry, so much is seafood and tourism — it’s killing us here. It is on Dauphin Island anyway.

Clark also said she visited the island to spend money, giving what she could to the local economy.

DAUPHIN ISLAND, Ala. Crews worked to clean up beached oil that washed ashore at Dauphin Island while people sunned and swam all around them. Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- DAUPHIN ISLAND, Ala. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service walked around Dauphin Island handing out information cards to visitors with phone numbers to call in case of oil or wildlife in imminent danger.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- A bird drinks from a small stream on the beach at Dauphin Island. A light oil sheen is difficult to detect in the bright sunlight, but can be seen in some images.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- DAUPHIN ISLAND, Ala. Crews work on the land bridge that will eventually connect Dauphin Island with another barrier island while Brown Pelicans and laughing gulls rest, fish and sun next to an enclosed tide pool. The green barrier fence was built by the National Guard to protect the area.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- DAUPHIN ISLAND, Ala. A brown pelican rests on a pier near oil booms at the base of the bridge to Dauphin Island.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

BP oil disaster swallows beaches in Mississippi

By Noelle Leavitt

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency.

Oily waters slowly crept onto the shore July 7, at Long Beach — near Gulfport and Biloxi, MS — where swimmers tried to enjoy the bright and sunny day despite the gloomy truth about the BP oil disaster.

Globs of oil muck started flowing onto the beach around 3 p.m., and by nightfall large sheets of oil slick started to swallow the white-sandy shore where thousands of visitors flock each year.

Ann Myers and her young granddaughter, Paris Williams, 1, waded in the water, only to find tar balls and glossy-oil mousse at their feet.

“I hate it. I think it’s just awful,” Myers said. “Because we always enjoyed coming here, and the grand babies can’t get out and play like they normally do.”

The little girl had oil smeared on her hands and neck from the contaminated water.

“She just picked up an oil ball. It was floating around in the water,” Myers said of her granddaughter.

The oily waters were deceiving to the eye, as many couldn’t decipher if the water was safe for swimming.

“It’s hard to see in the water,” said Greg May, Gulfport resident. “It’s really easy to see on the beach, though.”

Despite the obvious pollution, he still took a dip in the gulf.

“We’re going straight home to shower,” he said, adding that it’s really difficult not to get into the water despite the oil, because he loves the beach.

The Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality had yet to close the foul waters from public use.

The scene was much worse around 9 p.m., when the oil slick nearly tripled in size, prompting local officials to increase the number of clean up crews on the shore.

Government officials also increased the clean up hours to a 24-hour cycle.

- LONG BEACH, Miss. Ann Myers, and granddaughter Paris Williams, 13 months, play on the beach surrounded by globs of mousse tar balls on the sand and floating just below the surface of the water. The girl picked up some of the mousse, and it stuck to the skin on her hand, wrist and around her mouth, Myers couldn’t wash it off. Not far beyond where they played on the beach dozens of clean up workers in tyvek safety suits filled bags with the same oil mousse found where the child played.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency.

- LONG BEACH, Miss. Ann Myers, and granddaughter Paris Williams, 13 months, play on the beach surrounded by globs of mousse tar balls on the sand and floating just below the surface of the water. Not far beyond where they played on the beach dozens of clean up workers in tyvek safety suits filled bags with the same oil mousse found where the child played.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency.

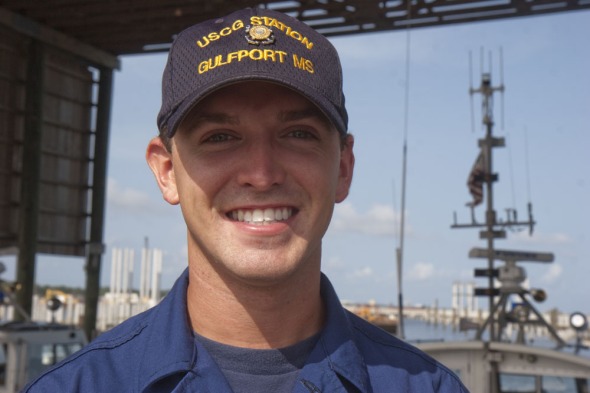

Coast Guards from Colorado work the oil slick

By Noelle Leavitt

Gulfport, MS — Two young Coast Guards from Colorado who are based in Gulfport, have a new whirlwind of experience under their belts from the oil spill.

Mike Svoboda, 20, from Parker, CO, cruises the oily gulf each day to document where the slick is at any given time.

“I’ve actually seen oil out toward the Barrier Islands, which are about six miles off shore. It’s little globs maybe about a couple inches in diameter, and it floats just beneath the water surface, and you can barely see it. And then when we went to Ship Island, which is one of the Barrier Islands, it’s actually all over the beaches.”

It’s the kind of oil nobody wants to touch.

“Sand sticks to it, everything sticks to it,” he said. “I don’t recommend picking it up. It sticks to your fingers real bad. It’s hard to get off.”

Coast Guard Matt Wietbrock, 23, from Westminster, CO has a completely different set of duties.

He answers the phones each day, filtering calls from civilians across the country who have ideas on how to stop the oil leak that’s now in its’ 80th day of gushing into the Gulf of Mexico.

“The phones are ringing constantly,” Wietbrock said. “Everyday someone has a new idea of how they can help stop the oil, and some of the people that call in have pretty good ideas, and some of the ideas are just crazy.”

Both men love to snowboard, and daydream of hitting the Colorado ski slopes in the winter.

Svoboda heads home to Colorado on July 9 for a much needed two week vacation.

Long Beach into night

- Long Beach, Mississippi, July 7, 2010. A large amount of oil washed ashore in Long Beach prompting the first night time cleaning. Lights were brought in for the workers, originally, the lights had amber colored filters on them to protect any sea turtles in the area. The filters were peeled off when the men in charge were told there was no danger from the lights.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- Long Beach, Mississippi, July 7, 2010.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- Long Beach, Mississippi, July 7, 2010.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- Long Beach, Mississippi, July 7, 2010.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

- Long Beach, Mississippi, July 7, 2010.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Louisiana’s Grand Isle goes through the oil ringer

By Noelle Leavitt

Reporter Noelle Leavitt handles mousse July 6, 2010 at Grand Isle Beach. Mousse is characterized as brown, red or orange in color with a pudding-like sticky consistency by Deepwater Horizon Response. Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Sticky blobs of oil lay upon the shoreline of Grand Isle, LA that is usually cluttered with children playing in the crisp ocean this time of year.

As the laughing gulls walk along the beaches, their webbed feet occasionally touch the polluting, pudding-like mousse that was breached from a broken oil rig nearly a mile deep off the Gulf Coast of Louisiana.

A portion of the contaminated shoreline is what’s called the “hot zone,” where tar balls and sticky oil pollute the beach.

Protective booms are spread along the shorefront, as well as signs posted warning the public to stay out of the effected areas.

Local residents now rely on BP for their income, said Grand Isle resident and home builder Wesley Bland, who has received two payments of $5,000 dollars in the last couple of months for lost work.

“This year was supposed to be a big year for me, better than last year. I have built 25 homes right here in Grand Isle,” Bland said. “I employ 17 people. Since the oil hit, I have six workers, and next month I may not have any.”

The father of four young children, Bland said $5,000 isn’t enough to pay his bills.

“You know, I put a sign out and I basically told (BP) to go to hell, but BP has came in and handed checks to all the local people, and continue to do so every month,” Bland said.

- The plastic barrier to prevent unauthorized persons from entering the contaminated beach is about 60 feet before the large inflated black and orange boom that demarkates the hot zone seen here July 6, 2010 near zone ten of Grand Isle Beach. The surf at zone ten is much darker in color the crest of the waves a dark brown in color. The beach is closed and there are plastic net fences set up to keep all unauthorized personnel away from the inflatable containment barrier which demarkates the hot zone. Nobody is allowed in the hot zone without the appropriate hazmat gear and equipment including facemasks and tyvek suits where the oil is the worst. There are “decon” crews whose primary job is to make sure none of the oil and chemical contaminants pass the barrier of the hot zone, cleaning the crews who clean the beach. They are the last defense between the oil and the public.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Louisiana tattoo parlor expresses frustration through art

By Noelle Leavitt

Tattoo artist Bobby Pitre has much to say about the BP oil spill, but he’s not doing it with words — he’s doing it with gobs of paint on billboards outside of his tattoo parlor in LaFourche, LA.

Huge paintings of President Barack Obama, the grim reaper, and an amputated body cover the front of his business — Southern Sting Tattoo Parlor — allowing him to use his own form of freedom of expression.

“It’s just a way to vent your frustration,” Pitre said. “It could’ve been prevented with a few more safety steps, you know. But they chose to ignore it, to save a few bucks, well a few million bucks, still, look at what it’s costing them now, you know.”

He also has a mannequin, wearing a gas mask, holding a dead, oil-saturated fish standing on the corner of his storefront.

“My little girl loves to fish. That’s pretty much what it is, the fish are toxic now with the oil. We can’t go out and fish,” Pitre said.

Passersby honk car horns throughout the day, sharing their annoyance with Pitre about the BP oil slick.

“On the side of the road, I could scream a hundred times a week if I wanted to,” Pitre said, adding that his art is a more useful way to assert his disappointment with the oil industry.

“People are pretty upset. There’s a lot of people that are actually working out there. As long as they’re making money, they’re alright right now. It hasn’t really hit home because they’re not starving right now,” he said. “It should’ve been stopped a long time ago, it could’ve been prevented — that’s why I’ve got this painting right here, ‘Deep Water Drilling 101’.”

Inside his parlor he has three paintings: Two of BP CEO Tony Hayward, and one of

Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindel. The Jindel painting is very supportive of the governor, and outside his shop Pitre painted “Bobby Jindel for President.”

“It’s pretty tragic the way it happened,” Pitre said. “Just the spill, the amount of oil that’s coming out is ridiculous.”

Pitre actually used to work in the oil fields. He was a welder and a fitter at the ship yards, so he’s very familiar with that end of it too.

Now, he spends his days as an artist, helping people express themselves with body tattooing.

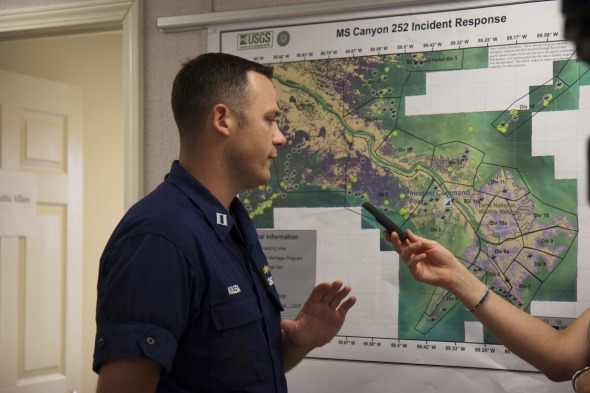

BP official expresses need for industry overhaul

By Noelle Leavitt

Venice, LA — A BP official stationed at the joint information center in Venice, LA expressed regret and sorrow on July 5 about the oil slick, which continues to gush oil into the Gulf of Mexico.

“It’s disheartening to me, very much so,” said Jon Parker, BP operations section chief for Venice emergency response. “We know we need to do better, and I think you’re going to see a lot of changes in the oil industry because of it and how we not only get the oil, but also how we protect against it.”

Joint information centers are set up along the Gulf Coast, where a federal government official, usually a U.S. Coast Guard lieutenant, and a BP executive work as a team in insuring the oil mess gets proper attention and remediation.

“We’re operating in a unified command structure,” said U.S. Coast Guard Lt. Frank Kulesa, who works in unison with Parker in Venice.

Although the pair work together in decision making pertaining to the oil disaster, the Coast Guard has ultimate authority over what happens with the clean up, Kulesa said.

“It’s an ongoing process. We constantly have to prepare for the next wave as we remediate what has already impacted the shorelines here,” Kulesa said.

The rehabilitation efforts for wildlife and the marshes is an ongoing effort that keeps Kulesa, Parker and hundreds of workers — charter boat owners, biologists, U.S. Fish and Wildlife representatives and hazardous material personnel — constantly on their toes.

“We’re in a unique position where the oil can constantly come, and we’re constantly fighting the tropical storms, the natural currents, trying to determine where the oil is going to go,” Kulesa said. “We’re deploying containment boom, using different strategies to keep it from getting into sensitive areas, such as the Delta National Wildlife Refuge, and then we’re getting skimmers down on the water to try to recover some of the oil before it hits shoreline.”

But no matter how hard they try, it’s virtually impossible to keep the oil from entering the marsh along the Mississippi River Delta, where Venice is located.

“A couple of weeks ago, we had a reprieve, where the oil had predominantly been moving towards Florida and Alabama, because of the winds. However it seems to be coming back our way, so we’re constantly looking for where the likely impact location is,” Kulesa said.

The delicate landscape of the Mississippi delta is home to a variety of wildlife. Small islands along Venice are nesting areas to various species of birds. One island in particular — Breton Island — was deemed a national wildlife refuge in 1904 by executive order of President Theodore Roosevelt, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Breton National Wildlife Refuge is the second oldest of 540 national refuges in the United States, and is located in a chain of islands 16 miles northeast of Venice. Extending northward toward the Mississippi Gulf Coast for 70 miles, it’s a nesting area for thousands of birds, including endangered species like the brown pelican.

Efforts to protect the island have been so extensive, that oil has yet to directly pollute the island.

“We’re averaging maybe two to three bird recovery a day, so we’re not getting the several hundred birds that we anticipated, at this point and time, which could change in the future,” said Bruce Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service public information officer for Venice.

Yet that doesn’t mean the birds are in the clear of contamination. Brown pelicans continuously dive for fish in the oily waters, bringing home contaminated food for their babies, Miller said.

Protecting marine life from the oily waters is an enormous task, and BP is well aware of the ongoing problems it faces.

“I think it was an eye-opening experience for not just BP, but it was an eye opening experience for the whole industry,” Parker said. “And we’re here to do what ever we can to make it right.”

- “I think it was an eye-opening experience for, not just BP, I think it was an eye-opening experience for the whole industry.” Jon Parker, BP Information Section Chief for Venice, LA. said July 5, 2010 at the Joint Operations Center in Venice, LA about the BP gulf oil spill and their role in the cleanup and the effects he has seen on the environment. Parker was formerly an Assistant Chief with BP and has nearly 23 years of service with them.

Photo by: Jenn LeBlanc/Iris Photo Agency

Travel update:

Here is our tentative day schedule for the gulf oil coverage:

Monday: Venice

Tuesday: Grand Isle

Wednesday: Biloxi/Mobile area

Thursday: Pensacola area

Friday: Destin area

We are following several stories both National and local (to Colorado) and even a few hyper-local for our friendly neighborhood newspapers.

If you have need of content in any of these areas please contact Noelle and Jenn directly through our dedicated email:

GulfOilCoverage@gmail.com

Welcome

This site is dedicated to the BP Gulf oil spill coverage of Noelle Leavitt and Jenn LeBlanc, two freelance journalists based in Denver. All content on this site is available for licensing, please contact Noelle or Jenn through GulfOilCoverage@gmail.com for information.

Any stories requiring embargo will be placed on this site after the allotted time, and will be available for further licensing, check back for new content.

Noelle and Jenn will be on the ground July 5, 2010 in New Orleans. If you have need of specific content, please contact us as soon as possible to make arrangements.